The rebuilding of the Roman fort of Epiacum was complete. The soldiers of the Sixth Legion with the Second Cohort of Nervians, the auxiliary troops who were to man the fort, were assembled ready for the ceremony of thanks and offerings to Hercules, the god of strength and defender against evil. A statue and an altar were to be dedicated in celebration of the completion of their work.

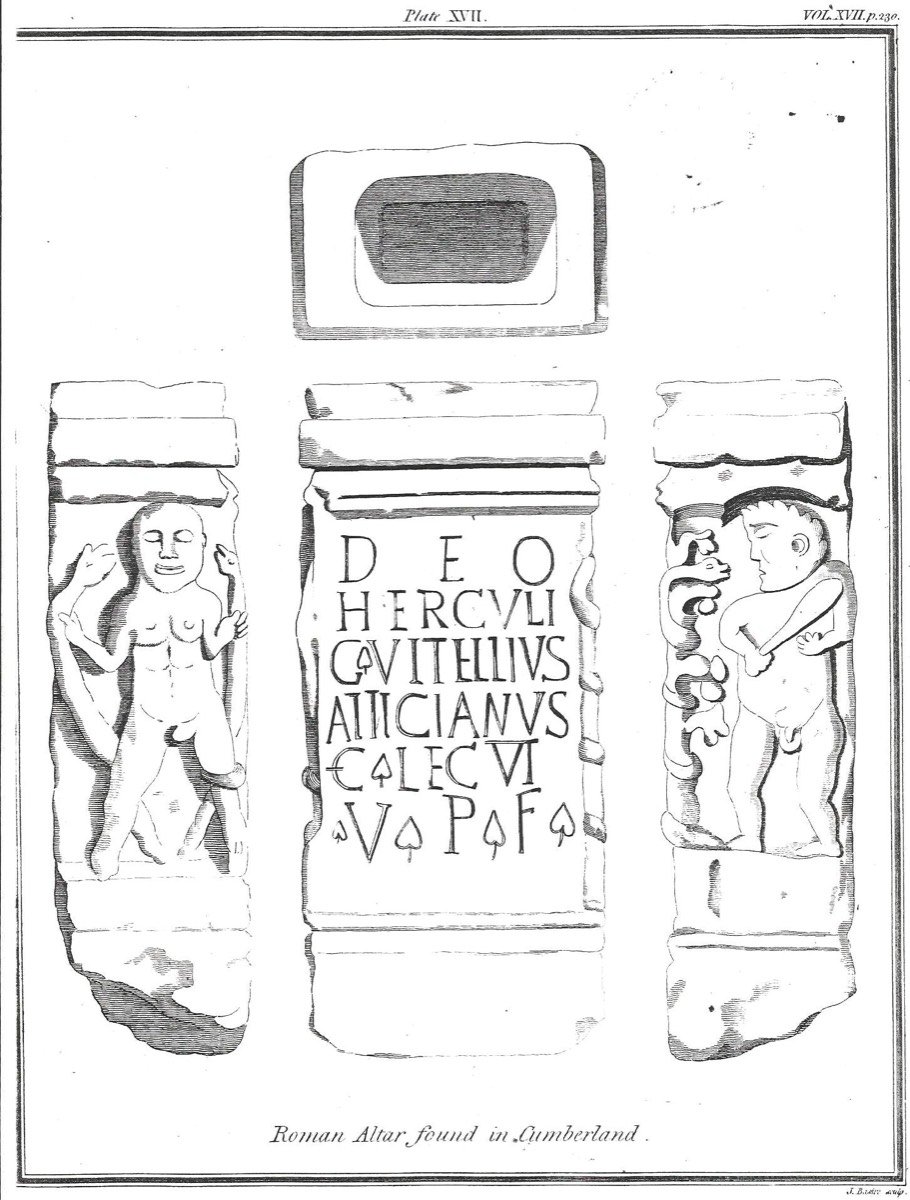

Caius Vitellius Atticanus, so called because of his birthplace in Greece, Centurion of the Sixth Vitrix, poured oil and incense into the thuribulum, or hollow, in the top of the altar, lit it and made the appropriate offering.

Carvings on the altar depicted snakes, which Hercules had overcome. Caius at one time had been bitten by a poisonous snake, and had been near to death, but because of his prayers and vows to Hercules he had recovered and was eternally grateful to the god for his survival. Having dedicated the altar, he commanded the Legion to get ready to move on.

In the years that followed, many soldiers paid their respects at the altar to Hercules, one of the most popular gods of the Roman army, and they meditated on the reliefs of two of his labours.

On one side the first labour of Hercules was depicted. As an infant he strangled two snakes that had been sent by the goddess Hera to kill him in his cradle. On the opposite side was Hercules in the last of his twelve labours, attacking a serpent that guarded the golden apples that he had been sent to fetch from the Garden of the Hesperides, the Daughters of the Evening.

The years turned into decades, which turned into centuries. The Romans abandoned Epiacum, known to us as Whitley Castle, in about 367 and left Hadrian’s Wall about 400 AD. The fort fell into neglect and ruin and was vandalised. The nearby statue of Hercules was smashed and the altar was toppled. Weeds grew about, grass covered the ruins and cattle and sheep grazed there. Yet the site remained occupied by native British tribes to be followed by Saxons and Vikings who lacked the building skills of the Romans. Then the Normans came, who left behind a fine patterned cast bronze skillet as a reminder of their presence. By a strange coincidence the pattern depicted serpents.

The altar to Hercules lay undisturbed and forgotten beneath the ground for 1500 years until 1803, when a farmer, while digging a drain or removing some of the useful ready cut stone, uncovered it and parts of the statue and thought they would make interesting ornaments. A few years passed and then in 1808, a gentleman visiting the area from the south of England, liked the look of the altar and bought it for the huge sum of £7 and took it away with the remains of the statue. In London in 1812, they caught the eye of Rev. Stephen Weston, who wrote a short paper about them to the President of the Society of Antiquaries in London, presenting it and a fragment of the statue’s hand holding a club to that society on 18th June.

The altar was resold at some time for £15 and again for £80 but to whom and where it went is not known. The altar disappeared for a hundred years then reappeared when it was recorded at Turvey Abbey in Bedfordshire in 1942. It stood there until 1961 when it was presented by its owner, Mr. Rupert Allen, to the Bedford Modern School collection, which became part of the Bedford Museum. So far as archaeological records were concerned, the altar had disappeared in 1924, while it was completely unknown to the people of its homeland of the South Tyne valley and Alston Moor. To the people of Bedford, Whitley Castle in Northumberland is meaningless. They simply see a block of carved stone, standing rather forlornly on its own as the only example of a Roman altar in the museum, and indeed the only altar in the whole county of Bedfordshire. The reason for its solitude is that Roman altars are military artefacts and the south of England was a peaceful place not in need of an army, while the north, well, somebody had to man the wall and museums up here are groaning under the weight of altars.

Then, in 1997, a local historian tracked down the Altar via the postmaster at Turvey, the monks and nuns at Turvey Abbey and a flash of inspiration. He visited the museum in Bedford to see it, touch it and photograph it – but failed to ask for it back!

Should a tribe of savage northern hordes raid the quiet south of England, pillaging, burning and that other thing to regain what is rightfully ours? Or should we arrange with the Tullie House museum in Carlisle to swap one of their surplus altars and allow us to return Hercules’ altar to its proper place?

Home

Home  Events

Events  Membership

Membership  Find Us

Find Us  About Us

About Us  Volunteer

Volunteer  Contact

Contact  Research Links

Research Links  Physical Archives

Physical Archives  Digital Archives

Digital Archives  1000 Year Lease

1000 Year Lease  Previous AMHS Websites

Previous AMHS Websites  Search

Search  Past Meetings

Past Meetings  Articles

Articles  Jubilee Exhibition

Jubilee Exhibition  Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery  Facebook Page

Facebook Page  Facebook Group

Facebook Group

Home

Home  Events

Events  Membership

Membership  Find Us

Find Us  About Us

About Us  Volunteer

Volunteer  Contact

Contact  Research Links

Research Links  Physical Archives

Physical Archives  Digital Archives

Digital Archives  1000 Year Lease

1000 Year Lease  Previous AMHS Websites

Previous AMHS Websites  Search

Search  Past Meetings

Past Meetings  Articles

Articles  Jubilee Exhibition

Jubilee Exhibition  Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery  Facebook Page

Facebook Page  Facebook Group

Facebook Group