ALSTON MOOR - OR IS IT?

When I first came to live in Alston I lived at Hundy Cottage on Front Street and I was puzzled by the name ‘Hundy’. I asked my landlady, the late Gertrude Maddison, if she knew what ‘Hundy’ meant. Gertrude didn’t know for certain, but at one of the Historical Society meetings, the speaker had given a talk on place names, and she had asked him. He hadn’t known off hand, but promised to try to find out for her. Some time later, she received a letter from him, saying that the best explanation he could give was that the word ‘Hundy’ came from old Norse, and could mean “the clearing in the woods where the hounds were kept”.

At first this seems a good explanation, as it isn’t just the houses in the area around The Hundy called such, but the adjacent fields are, or were, called Hundy Fields.

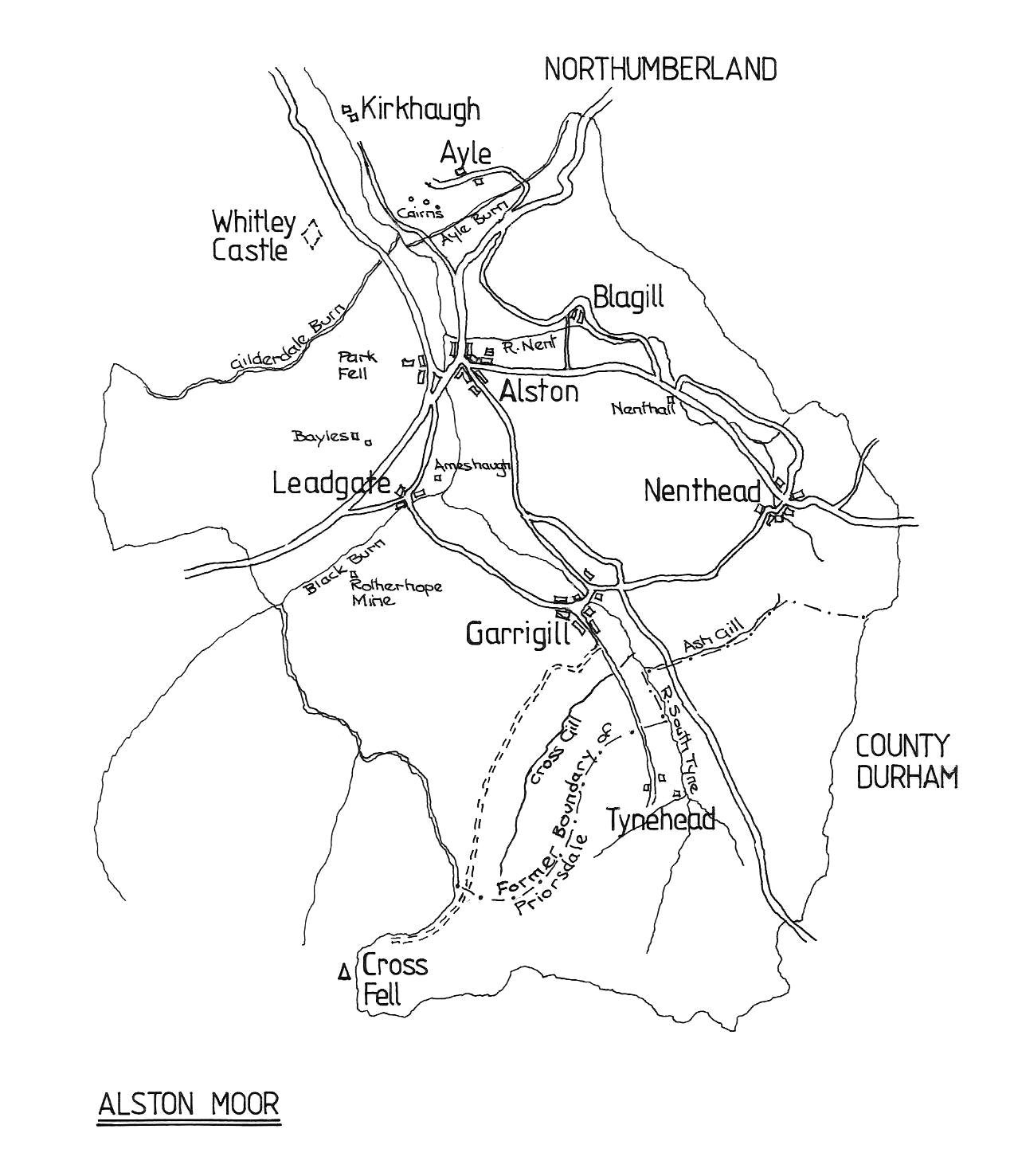

However, I wasn’t satisfied. Yes, the Vikings had had their fair share of naming places in Cumbria, -scale, -thorpe, -beck, -thwaite, -by, and on Alston Moor, we have names of hills, or ‘fells’, ‘fors’, meaning force, as in Nent Force, and narrow valleys, or ‘gills’. But the flaw in the argument in favour of a Scandinavian origin is in that a clearing in the woods is a ‘thwaite’. In any case, with Alston Moor, located at the meeting point of several regions, some local place names have Anglo-Saxon origins, such as ‘burn’ instead of ‘beck’, while Gerard of ‘Gerard’s Gill’, Garrigill, was a Saxon. So that Norse is present but not so strongly as the rest of Cumbria.

Precise borderlines meant little in those days and Cumbria has had a long history of being separate from England, and even up to the latter part of the 11th century, when the Norman occupation of the rest of the country was complete, Cumbria was firmly a part of Scotland; and not long before that it had been Rheged, an independent part of the Celtic, or British, kingdom of Strathclyde, while the north east of England was not so fully under Norman control as to be included in the Domesday Book. Alston Moor sits between Northumbria than Cumbria. The British were not such a tight-knit or closely organised race as others, which was one of their weaknesses and could account for them being able to survive only in relatively isolated, generally hilly areas that were less accessible, and less desirable, to invaders who could get easier pickings elsewhere. Alston Moor is such a spot, and place names would surely stand a better chance of retaining some Celtic/British influence where there had not been heavy overlays of succeeding races and societies.

Some time before this I had been given an Ordnance Survey booklet on place-name elements in Scotland, so I started at page one and worked through it, looking for anything that could be related to ‘Hundy’, but met with no success. I was about to put the book down when I realised that there were three sections to it. I had been looking only at the first section - more than half the book - on Gaelic, the second section, on Scandinavian, also proved fruitless, but in the third section, on Welsh names, I hit on success!

It was then that the penny dropped. In the early seventh century the Saxons from the north east were forcing the Britons back to the west, Scotland was occupied by the Picts and Scots, and the Saxon king of Northumbria, Ethelfrid, by occupying what is now Lancashire, drove a wedge between the British in Cumbria, and the British, who became the Welsh in Wales (Cambria). So, of course, any place name elements around Alston would have Welsh Gaelic, rather than Scots Gaelic roots, and so we have the rivers Tyne from ‘tei’ meaning ‘to dissolve’ or ‘flow’, and Nent from ‘nant’, meaning ‘valley’ or ‘stream’. And there in the book were the words ‘hwnt’, meaning ‘yonder’, and ‘daear’, meaning ‘land’. Say them quickly in the local dialect and you come pretty close to ‘Hundy’,‘Yonder Land’ - a perfect description of Alston Moor. Even today, whichever direction you come from, Alston Moor is ‘yonder land’, and the same must have applied 1,000 to 1,500 years ago, even more so when much of the land at higher altitude was used for summer shielings and left empty, or with far fewer people, during the winter.

While history records kings and wars and such, the ordinary people like you and me left their legacy by giving names to the places in which they lived, describing the places as they were at the time, who lived there, what type of trees grew around the site, the name of the person who first settled there, and so on.

Written records of Alston Moor start appearing in the first years of the 12th century, with silver from the lead mines destined for the Norman royal mint in Carlisle, and the great upsurge in demand for lead for church and castle roofs. It’s quite likely that the Normans and their miners arrived in this area of shielings, with its thinly scattered permanent population, to find that the Saxon ‘Aldwin’, or Danish ‘Halfdan’, had already established his ‘tun’ or ‘ton’, and where, over the years, the invaders of previous centuries, Anglo-Saxons and Norsemen, had intermixed with the indigenous British, and some British names had survived in the area known to the locals as Hwnt-daear, Yonder Land, Hundy.

Home

Home  Events

Events  Membership

Membership  Find Us

Find Us  About Us

About Us  Volunteer

Volunteer  Contact

Contact  Research Links

Research Links  Physical Archives

Physical Archives  Digital Archives

Digital Archives  1000 Year Lease

1000 Year Lease  Previous AMHS Websites

Previous AMHS Websites  Search

Search  Past Meetings

Past Meetings  Articles

Articles  Jubilee Exhibition

Jubilee Exhibition  Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery  Facebook Page

Facebook Page  Facebook Group

Facebook Group

Home

Home  Events

Events  Membership

Membership  Find Us

Find Us  About Us

About Us  Volunteer

Volunteer  Contact

Contact  Research Links

Research Links  Physical Archives

Physical Archives  Digital Archives

Digital Archives  1000 Year Lease

1000 Year Lease  Previous AMHS Websites

Previous AMHS Websites  Search

Search  Past Meetings

Past Meetings  Articles

Articles  Jubilee Exhibition

Jubilee Exhibition  Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery  Facebook Page

Facebook Page  Facebook Group

Facebook Group